James Low

James Low

Mexiquita

Secret Sound Recordings

Here’s a great debut recording from a rising local star, the first release from the fledgling Secret

Sound Recordings label; Marc Baker’s new entry in the local marketplace. Baker honed his A&R chops through years spent as the manager of Crazy 8s, as well as conducting KBOO’s “Church Of The Northwest” radio show. So it would stand to reason that he knows a thing or two about local music and how to market it to the public.

His choice of the understated James Low for the inauguration of his label was a wise one. Low is possessed of a simple Country/Folk style that melds well with those of the familiar coterie of side-musicians enlisted for this project— including such “usual suspects” as Little Sue Weaver on background vocals, Paul Brainard on pedal steel guitar and trumpet, Marilee Hord on fiddle and producer Nancy Hess on background vocals and other sundry instruments.

Low’s consistently well written songs are lowkey (so to speak), but edged with a sense of menace and drama. His attraction to the darker regions of the soul lends the material a distinctive human

quality. The sparse, understated arrangements play to Low’s many strengths: the chief of which are his highly emotive singing voice— a rich baritone, and his poet’s eye for telling detail.

The first track,“Mexiquita,” is a good example of the aforementioned. Over a solitary acoustic guitar Low sings a forlorn ballad about a doomed love affair. Hord’s accompanying melancholy violin tones seem metamorphosed in the mix into moaning cries. Little Sue harmonizes sweetly, ala Emmylou Harris. Melodically, the song occasionally recalls faint strains of Paul Simon’s “Lincoln Duncan” and “Scarborough Fair.”

Hess’ smooth standup bass and soft brushwork on the trap set, in addition to Brainard’s plaintive trumpet, lend a peculiar Jazz ambiance to the subdued “Built To Last.” Brainard’s pedal steel phrasings add an early Neil Young Country feel to the beautiful “Carver Blues.” Tension builds slowly and solemnly in the nervous energy of “Soledad,” a song that bears some stylistic similarities to Neil Young’s “Last Trip To Tulsa,” from his first solo album; but, perhaps, an even grimmer scenario.

The gritty symbolism behind “Miner’s Lullabye” is the type of composition to which every songwriter aspires in one way or another. It sounds as if it could have been written a hundred years ago— always a part of the public vernacular. Like “My Darlin’ Clementine” or “Streets Of Laredo.” “Sing little bird/Sing for the skies in your freedom/It’s dark in this hole and our bodies are bonded/Yours to the miner/And mine to the coal.” The melodic aspects of the song resemble Young’s “Runnin’ Dry,” from his second album Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere.” But the sentiments of hopelessness and desperation have never been more succinctly expressed. Timeless.

“Endless River” traces a laidback Country vibe, closer to the early Eagles than Merle Haggard; but abetted nicely by the versatile Brainard’s stellar pedal steel guitar-work. “Blackcoat” explores a Western Cowboy” motif, along the lines of “Tom Dooley” or “El Paso.”

The Folk/Pop sensibilities of “You Said” mirror those of the Beatles and the Beach Boys, delicate and well-delineated.

James Low’s is an apt moniker. None of his songs are likely to knock one over the head with sturm und drang. But the accomplished craftsmanship in his work is undeniable. And the concise elegance in his delivery is indisputable. Whether there is a place in the technicolor Rock world for a black and white, film noir scenarist such as Low, remains to be seen. But his abilities are securely fixed. That much is certain.

Feller

Feller

Furthermore

Self-Produced

Here is a fine effort from and up-and coming quartet of Folk Rockers. Ably abetted here by exSlackjaw bassist Robert Bartleson, who engineered this recording, the band, consisting of drummer Daniel Gero, bassist Carter Hill and singer/songwriter guitarists Scott Barton and Jack Wilcox. Individually and together they create some very interesting original music.

The album kicks off with “Me For Free,” a rousing Barton tune, propelled by Gero solid drum hits and the incessant jangle of acoustic rhythm guitars. Wilcox counters with “Old King,” which

feels a bit like the work of Dave Matthews.

But the record really gets going with the whacked out intro of “Headed West.” Against a palette of splattering electric guitar wanks, a determined little electric guitar motif sneaks out of the mix, to eventually become surrounded by syncopated drums, sparse bass and snappy acoustic guitar hammers into the body of the song. Extremely cool.

Barton’s “Heavy Gone” rides upon a flickering acoustic guitar ornament and Hill’s stylish upright basswork. A moody number, the song falls like an Autumn fog around the ears of the listener. Fingerpicked acoustic filigrees dance around thick electric guitar tones. A very seductive song. Wilcox’ instrumental “Medora” maintains the pensive atmosphere.

Nice, subtle touches of backwards guitar and a vocal line which closely mirrors that of Thomas Dolby on his early ‘80s number, “Mulu The Rainforest,” provide the impetus on Barton’s “Scar.” A great piece of poetry acts as the lyric. “Drove his first nail into clear grain frame/Cladding over shadow/Peeking edges jagged peaks building shelter/In the valley deep and becoming giant in his scar.”

The momentum of insistent 6/8 time pushes the initial verses of Wilcox’ “Fine,” breaking into 4/4 deeper into the song. Wilcox adds a gruff vocal to the jagged guitars of “4 AM.” A similar feel drives “Get Up.” “Multnomah” is a fleeting house of a song.

Feller exhibit tremendous inventiveness and originality with this outing. Whatever their musical and poetic influences, they have worn them well absorbed into their own individual psyches, And with this recording they have created one of the best local albums of the year.

Mr. Rosewater

Mr. Rosewater

Mr. Rosewater

Self-Produced

Here’s an entry from the winners of this year’s “Most Likely To Have Graduated From The

MHCC Jazz Program” award. What we have are some pretty solid young Jazz musicians spreading their wings and expecting to fly. And they, especially the core group of drummer Evan Louden, bassist Jason Mellow and guitarist Andrew Field, evince

solid training in their crafts, with talents that would seem to indicate eventual success, either individually or collectively.

Still, in the case of Mr. Rosewater, committing their musical exercises to disc seems a tad premature. It’s as if half the band were missing or that these are the basic tracks for a more complete project. Field and company don’t seem to lack for ideas. And their execution is relatively sharp.

But there are no vocals here. It is left to Field and saxist Thomas Smith to carry the lead load. While their efforts are admirable, they do not at this time command the array of tones and chops necessary to require the spotlight more than occasionally.

Thomas, in particular, seems to be playing by rote the lessons he learned in school; staying entirely within a comfort zone, without stretching the least beyond those boundaries. He is a good Jazz player, but he has the same tone on practically every track. And he never seems to get the least bit excited by his musical prospects. Field fares not much better.

“Barbecue” seems to take it’s cue from Brubeck’s “Take Five,” utilizing 5/4 and 10/4 time signatures. But Field is no Brubeck in the melodic rhythm role and Smith is not yet Paul Desmond on the sax, though it’s possible Smith fancies himself as a disciple perhaps. Evan Louden, however exhibits real talent in holding down the fort behind the drumkit. “Pagoda” displays some vocal promise, with a bit of a gang rap. And “Rhombus” allows Smith room to show off a smart lick.

Most of all, Mr. Rosewater desperately needs a vocalist— someone to impart a lyrical viewpoint. A junior Donald Fagen would be perfect. But anyone with the disposition and faculty to handle the role would work better than nothing. A keyboardist would be good too. Someone to add coloration and take over the lead chores form time to time. These things would ostensibly allow Smith and Field space to play less and make the most of their spots.

Both Field and Smith could work to alter their tones from time to time. Field rarely strays from a beefy smooth lulling sound, that is extremely well suited to Jazz solo work, but lacks the bite to truly grab the listener. Smith could try to utilize some devices: delays, flangers, etc. The Seattle saxman Skerric of Critters Buggin’ used to sound like Jimi Hendrix in the band Sad Happy. But whatever they do, Mr. Rainwater needs to do something to alter the stifling fog they often create.

The Orange Collection

The Orange Collection

Do You Still Dream…

Self-Produced

The Orange Collection are a pair of enterprising young lads who demonstrate a propensity for a

Pop song. While they don’t hit homeruns with every swing, they connect with enough frequency to hit for a relatively high average. The boys would seem to have an agenda and a message to disclose to the world.

But they keep it reined-in for the most part. The fact is they succeed best when they sing about the things they know and least when they proselytize to the heathen hordes. However their touch is, for the most part, comparatively light and innocent. So they should be forgiven. They know not what they do.

Vocalist Sean Dickson plays bass, keys and guitars, while Shane Wolfe provides the drums, percussion and background vocals. Together they manage to create a full band sound. It’s an eclectically ingenuous sound, as if Boy George and Prince took turns fronting the Three O’Clock. Dickson’s vocals alter between a boyish coo and a thick, adenoidal, West Coast scouse.

As a songwriter, Dickson understands the structure of a Pop song, delivering carefully crafted material. The subject matter ranges from odd boy/girl and other interpersonal relationship numbers: “Dancing Girl,” “The Night I Met Maria” and “Do You Still Dream,” and broader swathed testaments such as “Won’t Hurt My Soul” and “Keep It Together.”

The latter is best served by “Won’t Hurt My Soul,” over a solid bass/drums interchange, Dickson sings. Last night I didn’t get no sleep/Is the man up above just nodding his head at me/And how do you think I could ever get any peace/When this whole world’s just crashing down on me.”

The former is captured particularly well on “Dancing Girl,” a curiously cautionary tale. “I know this girl who loves to dance/She sells herself to fellows for romance.” Certainly, that’s delicately put. Over a chunky guitar figure and a creaky organ filigree, Dickson further delineates. “She’s so confused in her own world/Always wondered what it would be like to be a girl/But she never had the chance to go to a prom/Or have her best friend be her mom.” Fierce words there.

But the band’s attempt to wrest a “Smooth,” Santana-like Latin feel from “The Night I Met Maria” fails to get off the ground. Over snappy acoustic guitars and a cha-cha beat Dickson tells a somewhat surreal and perhaps symbolic tale. “Smoke filled the air, the lights all dim/Knew I’d entered sensual freedom/My eyes they took a glance/Across the ballroom she stood in elegance/And owe those eyes take me over so easily/My hear cries do you see her, bonita/This is the night that I met Maria.”

The Orange Collection show promise. But the object for most songwriters, ideally, is to reach as many listeners as possible. In order to do that it is necessary for the writer to know about the subjects upon which he sings.

In any religion or spiritual quest, it is good and right that a person should experience his emotions. The best song material is created when the writer honestly confronts the impressions that arise from those emotions, rather than to attempt to cobble them into some sort of a parable or a sermon.

An artist must sacrifice his Self in order to perceive this union (or battle) between the intellectual and emotional aspects of the soul. Once young Sean Dickson endeavors to observe those emotional impressions rather than to intellectualize them, he will have become the artist he hopes to be. Once he learns to write about those impressions without judgments or preconceptions. At that moment he will have found his true muse.

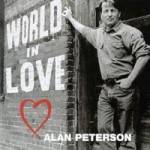

Alan Peterson

Alan Peterson

World In Love

Self-Produced

September must be Christian music month at Two Louies, for here we have another round of pæans to our lord. Here, the focus is more mature. Peterson, who is perhaps best known (in the more mature corners of the Portland music scene) as the owner of the club Sweet Revenge, a one-time haven for Folkie singer/songwriter types in the late ‘70s.

Somewhere along the way since those long departed days, Alan must’ve seen the light. For here we are blessed with a baker’s dozen, plus one, of impeccably recorded traditional white gospel influenced songs, all penned by singer/songwriter Peterson. Unlike most local albums produced in this genre, the recording and performance values are first-rate. The songs, for what they are, are fairly well-written.

Nearly all the songs refer to love and feelings, light and life. Lyrically they tend to be so ubiquitous as to be interchangeable. The song titles alone are a one-trick pony: “Do You Feel The Love,” “It’s A Wonderful Life,” “Hold On To The Feeling,” Precious Love,” “That Certain Kind Of Light, “That’s The Way The Life Goes” and so on.

Such innocuous adjectivism renders Peterson’s material so idiosyncratically euphemistic, that it makes no literal sense whatsoever in the lay world. Hence, the songs are reposited into a realm where the inhabitants are acquainted with such esoteric symbols. That’s called a church.

The idea, it would seem, would be to attempt to attract a wider audience. George Harrison did it with “My Sweet Lord.” He accomplished that by co-opting one of Phil Spector’s most brilliant productions— the Chiffons’ “He’s So Fine.” The Edwin Hawkins Singers did it with “Oh Happy Day.” They were a legitimate black gospel troupe.

As was stated in the Orange Collection review, it is incumbent upon Christian songwriters, if their intent is truly to venture product into the secular world, to dig a little deeper within their collective psyches to derive something that rings true among the common plebeian, not just those who choose to go along with a specific belief system. Otherwise, one is merely preaching to the choir. With the level of talent among the musicians involved with this project, that would be a real shame.